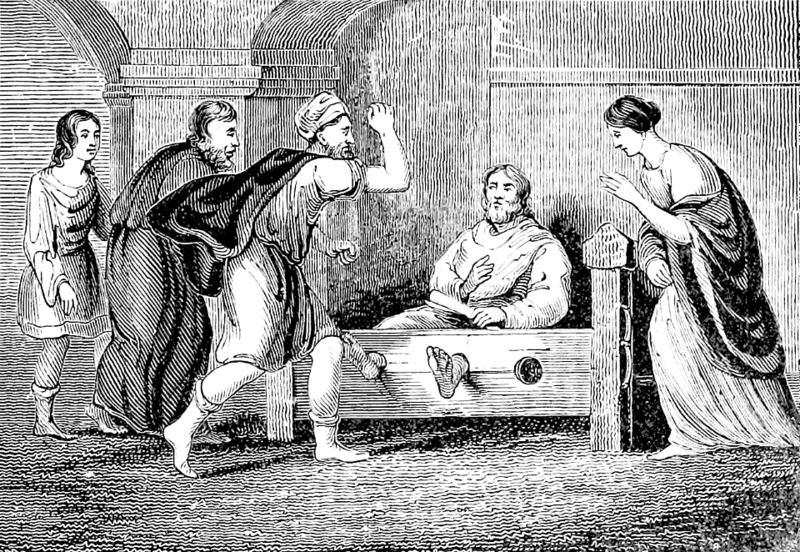

Image: Jeremiah in the stocks, public domain

As we continue in the book of Jeremiah, one thing has become crystal clear: poor Jeremiah didn’t sign up for any of this. He hadn’t chosen to be a prophet; God had chosen him. He didn’t want to stir up trouble; he wanted a peaceful, quiet life. He didn’t even want to preach, but whenever he tried to keep silence, the unspoken Word of God gave him spiritual heartburn! He didn’t sign up for abuse and mockery at the hands of those who ought to have known better—the Temple priests. He didn’t sign up for the plots against his life from the residents of his hometown of Anathoth. And he certainly didn’t sign up to be thrown in a pit and locked up with a bread and water ration.

And he certainly didn’t sign up to be hit and put in the stocks. This happens after he upsets Pashhur, one of the priests, with a prophecy. That prophecy involved him taking a jug, going into the Temple courts, and smashing it in the sight of everyone. The point is that the relationship between God and Judah has been irretrievably broken, “like a jug that cannot be mended”.

But Jeremiah feels that his own relationship with the Lord is broken as well. The poem in verses 7-13 is stunning. Jeremiah accuses God of enticing him. Of luring him into being a prophet under false pretenses. Of using him and then leaving him to suffer the consequences. Jeremiah’s lament over his humiliation, pain, and disrespect show us an unvarnished honesty with God.

So, what do we do with this? This is a hard word of Scripture. Is God a two-faced kind of deity, who promises with one hand and takes away with the other? Or is there something more going on here with Jeremiah’s mistreatment and lament?

The maxim we learned in Sunday School is true: God is good (all the time) and all the time (God is good). Yet, God is not a simple god. God is not subject to our expectations or desires. Throughout Scripture and history, God is constantly subverting our expectations to show us something more. And the subversion I’d like to focus on is this: as Jeremiah finds out, our relationship with God is not about increasing our personal happiness.

The cult of personal happiness is everywhere, it seems. For instance, a lot parenting these days seems to involve helping our children find their “thing” that we’re sure will bring them happiness, even if it means sacrificing virtue or character development. We look for happiness in the things we buy or the vacations we take. And when that doesn’t work, we can narcotize and numb ourselves either with physical substances or with behaviors. Unfortunately, that often also extends to our relationship with Jesus Christ. It’s easy to think that Jesus is there simply to help us feel better about ourselves. To give us a placebo of forgiveness that lets us stay mired in our old ways. The German pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer would call this “cheap grace”, which he defines as “grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without the living, incarnate Jesus Christ.”[1]

But that’s not the purpose of our relationship with God in Christ at all. The purpose of that relationship is to equip us to live out and proclaim the Word of God which brings salvation to a sin-sick world. It’s not about temporary happiness or a veneer of peace, but about God’s own shalom. And that shalom doesn’t paper over things. Jeremiah is willing to speak hard words to God, and God speaks hard words back to Jeremiah. At first glance, this appears to be a lack of peace and unity in their relationship. But the honesty between them—the honesty found in the Word of God—roots Jeremiah in the shalom of God.

This shalom of God is at the root of Jesus’s work. In our reading from John’s Gospel, Jesus himself is troubled by what lies ahead. Actually, troubled is not quite the right word; it should read something like “deeply disturbed”. He is deeply disturbed at the thought of what lies ahead for him—betrayal, humiliation, torture, and death. Yet, he knows why he has come to this moment. All is about to be fulfilled. He says, “Father, glorify your name.” The implication is clear. The glorification of God will be accomplished by the suffering, death, and resurrection/ascension of God the Son, Jesus Christ. And by all this, Jesus will bring people under that very shalom. As he says, “And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself.”

All will be drawn to Christ. That’s a wild thing to say, considering the state of the world! Yet, Jesus says it. And it continues to happen. Think of ourselves. We live half a world away from where Jesus was crucified and raised, some two thousand years after those events. In that time, the church has been distressed by heresy after heresy, from the attempted cooption of the faith for particular ideologies to the prosperity gospel, which is nothing more than the cult of happiness. Yet, we have been drawn to Christ. Sure, sometimes we may feel like Jeremiah. Sometimes we may feel like we’ve been tricked into the path of discipleship, carrying a cross we didn’t ask for. Let’s be clear: discipleship ruins lives! It ruins the old kind of sinful life we get comfortable living. It ruins the old worldviews we have about how the church and world ought to be. Yet, in that ruination of our lives as we know them comes something greater—the shalom of Christ which brings salvation to the world. That shalom of Christ is the fulfillment of what God has done for us and what God continues to do in, through, and with us as the church.

The life of faith is hard sometimes. Yet, in Christ, we are empowered to live it, not merely for ourselves, but for the whole world as well. Amen.

© 2025, David M. Fleener. Permission granted to copy and adapt original material herein for non-commercial purposes with appropriate credit given.

[1] Clifford J. Green and Michael P. DeJonge, eds., The Bonhoeffer Reader (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2013), 461.